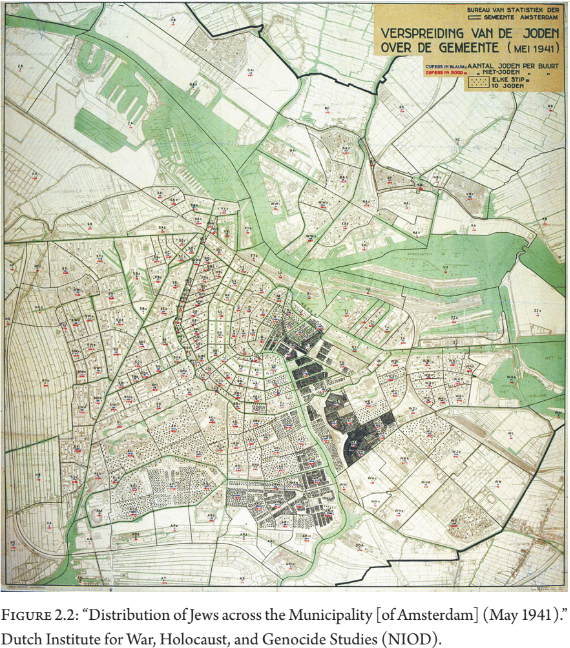

We begin in the 1930s and early 40s, when algorithmic processes — using Hollerith punch cards, tabulating machines, and computational statistics — played a critical role in tracking and registering Jews, compiling deportation lists, and reducing people to ‘bare data.’ Under Nazi occupation, the Dutch state’s registration authority and its Chief Inspector for Population Registration, Jacobus Lentz, assiduously carried out the Nazi orders to register all the Dutch Jews, compile interoperable records of the registration and census data, visualize that data as maps, and process that data to form deportation lists. This is an emblematic — and calamitous — moment in which data gathering, data analysis, data visualization, and computational processing became complicit with genocide. Today, however, much of that same data has been transformed into a kind of digital refuge through various memorial projects that give rise to new stories and commemorative practices spanning the digital and physical worlds. To understand this dialectical potentiality, we ask: What does it mean for a database to be ethical (and unethical)? How can computation be used for life-affirming ends? How can data be gathered, indexed, and processed in ways that open up new possibilities for memorializing human life and adding to our understanding of the cultural record?